Scientists have long been mystified by the possibility of a liquid ocean beneath the icy and reflective surface of Jupiter’s sixth moon, Europa. Now, scientists have revealed a new theory, devised from old evidence, that suggests liquid water lakes may be much closer to the surface than originally thought.

Hidden Oceans

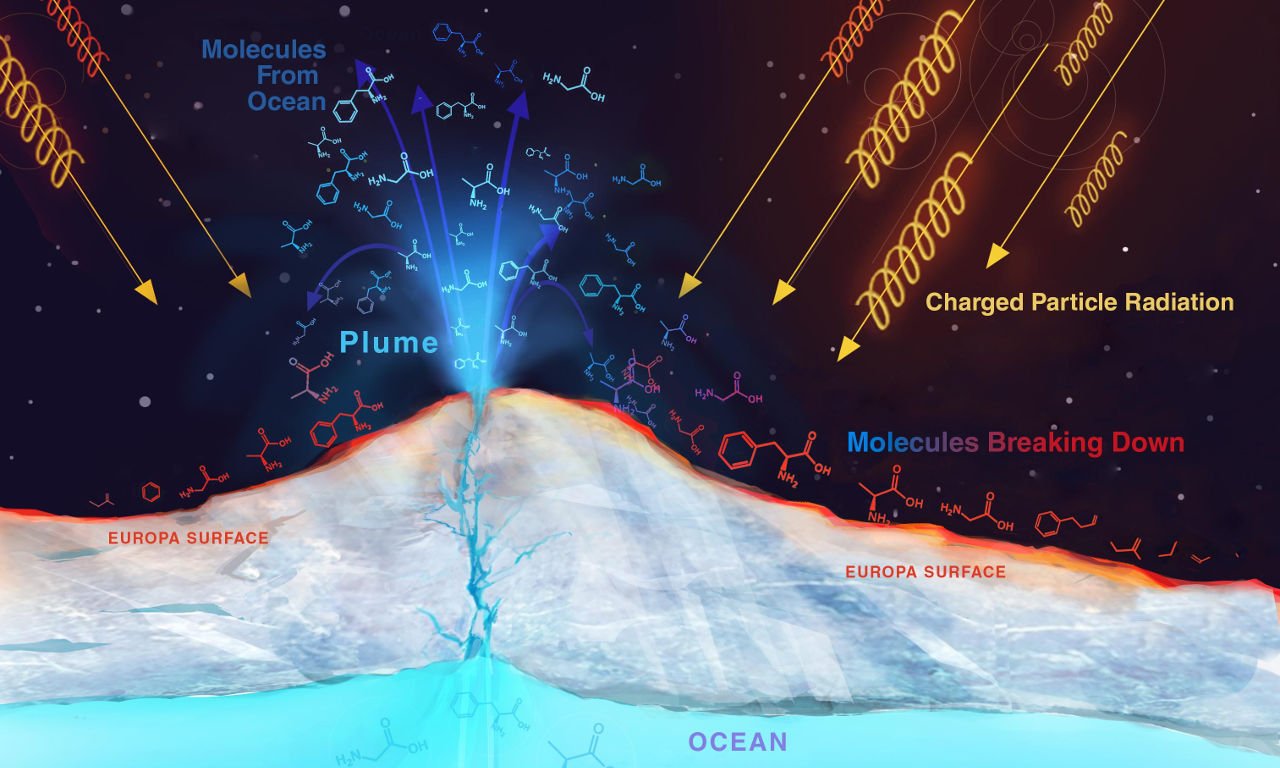

They’re referring to the possibility of ice-trapped lakes located 1.9 miles beneath the moon’s roughly 60-mile-thick frozen shell.

The theory was developed through comparisons of similar phenomena on Earth — such as “subglacial volcanos” and the ice shelves of Antarctica — with the chaotic regions, or “chaos terrains,” of Europa.

Data and images collected by the Galileo spacecraft, sent to Jupiter in 1989 (which arrived at its destination in 1995), allowed them to make those comparisons and better understand the “paradoxes” found on Europa’s surface.

So, what’s the big deal with underground oceans and lakes of chaos?

Were an ocean to exist beneath the moon’s inhospitable surface, organic lifeforms could proliferate, but only if nourishment could find a way through the ice. Subsurface lakes, and the ice shelves collapsing into them, would allow for that possibility. Such lifeforms would be very similar to the microbial life found deep within our own oceans.

NASA is hoping to investigate these regions in greater detail during a mission scheduled to begin in 2020.

A Brief History Of Europa

Europa is known as the sixth Galilean Satellite, one of four moons Galileo Galilei discovered in January 1610. The others were named Lo, Ganymede, and Callisto, each named after the lovers of Zeus from Greek mythology.

Europa is physically smaller than Earth’s moon, containing a silicate mantel similar to most terrestrial planets, as well as a metallic core. Its surface is also one of the smoothest in the solar system, despite the scattered regions of chaos.

Unfortunately, radiation from Jupiter causes Europa’s surface to emit around 540 rem per day, enough to make humans sick were they to experience prolonged exposure. Beneath that irradiated surface, however, lies the possibility of a liquid ocean, which could provide organic life the opportunity to flourish in otherwise inhospitable conditions.

The most interesting characteristic of Europa, which may lend further credence to the possibility of a liquid ocean, is its orbit around Jupiter. Scientists have long wondered whether or not gravitational effects of the moon’s eccentric orbit may cause internal, “tidally generated heat,” enough to allow a liquid ocean to form beneath its surface.

According to Wikipedia, Europa’s rotation may provide further clues into what lies beneath:

A non-synchronous rotation has been proposed: Europa spins faster than it orbits…suggests an asymmetry in internal mass distribution and that a layer of subsurface liquid separates the icy crust from the rocky interior.

In the 1970s, Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 became the first human spacecrafts to visit Jupiter, and in 1989, the Galileo spacecraft set out to provide incredibly detailed images of the Galilean satellites, providing the foundation for today’s latest theory.

NASA intends to return sometime in the next decade to confirm or deny the existence of the Jovian moon’s hidden ocean and, by extension, life on Europa.